Cochlear Implant

A cochlear implant is not a hearing care aid. A hearing aid makes it louder for a hard-of-hearing person.

A cochlear implant is an electronic tool that transmits sounds directly to the part of the inner ear that accesses the auditory nerve.

The F.D.A., U.S. Food and Drug Administration initially certified cochlear implants for use in adults in the mid-1980s.

In 2000, the devices were approved for use in children as young as 12 months old. About 40 percent of kids who are born profoundly deaf now receive the implants, and more the 38,000 devices are being used in children.

Approximately 58,000 devices have been implanted in adults.

As confirmed by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication illnesses, children who receive implants before they are a year and a half can better hear, speak, and understand music and sounds than children who receive the implants are older.

HOW DOES A COCHLEAR IMPLANT WORK?

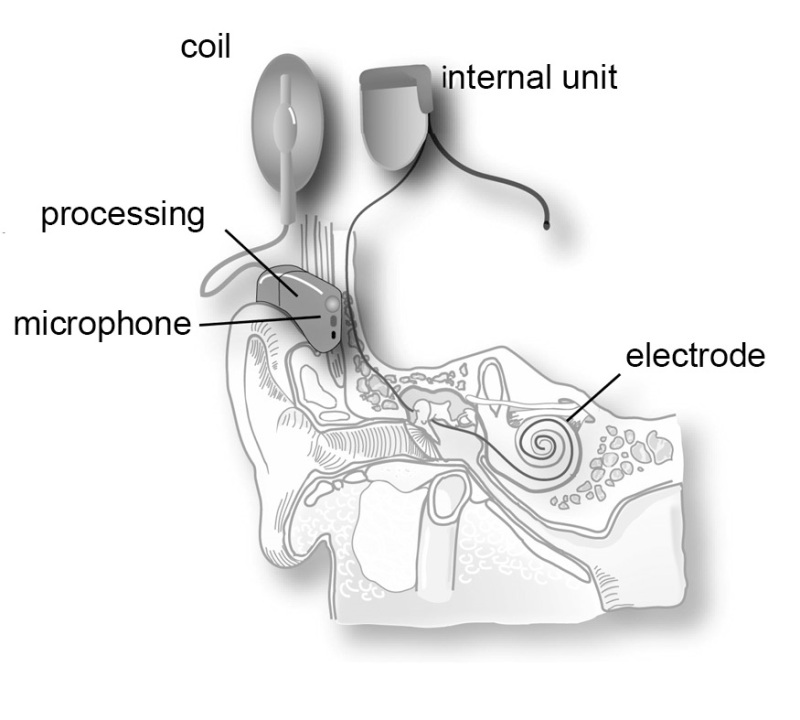

A cochlear implant consists of up of two parts: the external speech processor, which sits behind the ear, and the internal receiver, which is implanted in the mastoid bone of the skull.

The external speech processor includes a microphone that picks up voices and sounds from the environment.

The microphone sends the sounds to a digitizer, which processes the sounds and turns them into electrical impulses, which it then transmits to the transmitter coil.

The transmitter changes the impulses into radio waves, which it then sends to the internal receiver.

The internal receiver is made of two parts. The larger of the two is the receiver itself.

Implanted under the scalp, in the skull behind the ear, the receiver transforms the radio waves from the transmitter into electrical impulses (it also contains a magnet that attracts and holds the transmitter in place on the outside).

Attached to the receiver is a cable that carries impulses to electrodes that have been inserted into the cochlea.

The cochlea is the ear that usually transforms sound into electrical impulses that go to the ear’s main nerve, the auditory nerve.

Electrodes are threaded into the shell-shaped cochlea and take over, providing electrical impulses to the nerve with an implant.

A cochlear implant cannot restore normal hearing. However, it allows a person to distinguish voices and sounds in the environment, understand warning signals, and understand conversations on the telephone. For some people, it even makes it possible to determine music.

WHO CAN BENEFIT FROM A COCHLEAR IMPLANT?

Cochlear implants can help you if you:

- can hear with both ears, but not clearly

- are losing your hearing and are not finding hearing aids helpful

- rely on lip-reading to understand what people are saying, even though you have hearing aids

- even with lip reading, you miss more than half of the words that people speak

However, this treatment isn’t for everyone. There are risks involved, and each person must decide for themselves if they are willing to commit to the necessary therapy after surgery.

First, remember: the implants do not restore hearing to normal.

There is a period of adjustment as the brain learns how to interpret the signals; for this reason, the younger a person is when the implant is done, the better the chances of success.

For some people, cochlear implants do not help with hearing at all.

Training and therapy are required after surgery, including aural rehabilitation. During aural rehabilitation, you will learn how to interpret electrical signals and how to communicate better.

If you play sports, you may damage the implant accidentally; before swimming, bathing, or showering, you may have to remove the external speech processor to prevent it from being damaged unless it is waterproof.

The processor is battery-powered, and the battery will need to be changed and recharged regularly.

If you have middle ear infections, do not have an auditory nerve, or, in the case of children, have developmental issues that would make it difficult to take part in aural rehabilitation, a cochlear implant is probably not for you.

Some people decide against cochlear implants for personal reasons.

Another factor to consider is cost. Without insurance, the price of a cochlear implant in 2020 ranged from $30,000 to $50,000.

However, most major insurance companies will cover the cost. For people under 21, all state Medicare agencies must cover the cost, which includes the device and surgery and activation and aural rehabilitation.

WHAT IS COCHLEAR IMPLANT SURGERY LIKE?

During surgery, the subject is under general anesthesia. The surgeon shaves the area where the implant will be placed and cuts a flap of the scalp to access the skull.

The surgeon then carves a slight depression into the bone to hold the receiver. Next, the surgeon drills a pathway through the bone to the cochlea, and passes the cable through it, and positions the electrodes within the cochlea.

Then the incision is closed up. Cochlear implant surgery takes about an hour, and patients usually go home the same day.

After the surgery, the external processor is provided when the patient goes to a cochlear implant audiologist, calibrating the device and activating it.

As with any surgery, there are physical risks to the implant procedure, such as reactions to anesthesia, infection, bleeding, and swelling.

However, hazards more unique to this procedure include:

- Dizziness.

- Changes in taste.

- Numbness around the ear.

- Damage to facial nerves that lead to movement problems.

The area of the implant may become infected, as can the membrane that surrounds the brain. In some cases of infection, it may be necessary to remove the implant.

Candidates for cochlear implants undergo examinations and tests to determine how extensive your hearing loss is and if a cochlear implant would be suitable for you; these may include imaging studies, such as MM.R.I.s

You will meet with an audiologist, who is an expert in diagnosing and treating hearing and balance issues; an otologist, who specializes in the medical and surgical treatment of ear disorders;

and a speech-language pathologist who specializes in assessing, diagnosing, and treating speech and language disorders, such as the ability to understand other people.

You may also meet with a counselor or psychotherapist.

An essential part of succeeding with a cochlear implant is to understand its limitations and manage your expectations.

Auditory rehabilitation is vital to the process, and patience is necessary to adjust to your new device.

Resources

Websites

“Cochlear Implant Surgery.” Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/cochlear-implant-surgery (accessed November 13, 2020).

“Cochlear Implants.” BabyHearing.org, Boys Town National Research Hospital. hhttps://www.babyhearing.org/devices/cochlear-implants (accessed November 13, 2020).

“Cochlear Implants.” MedlinePlus. November 6, 2020. https://medlineplus.gov/cochlearimplants.html (accessed November 13, 2020).

“Cochlear Implants.” National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. March 6, 2017. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/cochlear-implants (accessed November 13, 2020).

Organizations

Boys Town National Research Hospital, 555 North 30th Street, Omaha, NE, 68131, (531) 355-1234, Fax: (301)480-1845, https://www.boystownhospital.org.

NIDCD Information Clearinghouse, 1 Communication Avenue, Bethesda, MD, 68131, (800) 241-1044, TTY: (800) 241-1055, nidcdinfo@nidcd.nih.gov, https://www.nidcd.nih.gov .