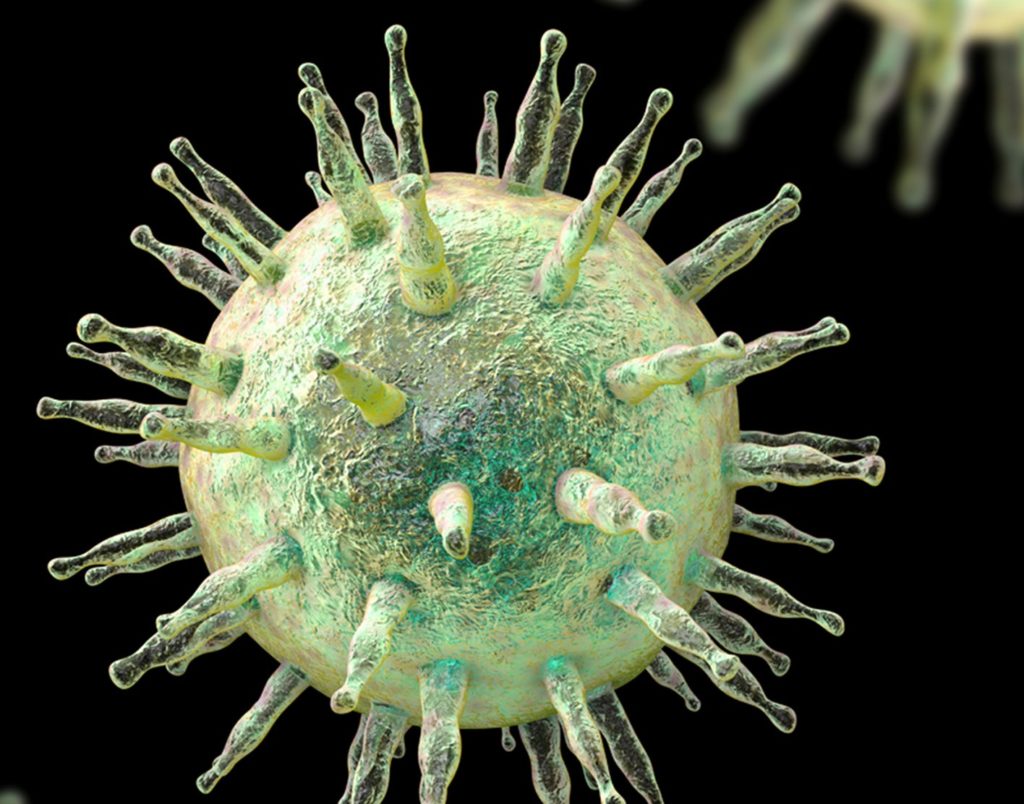

Epstein-Barr Virus

DEFINITION

Epstein-Barr virus, or EBV, is an offshoot of the herpesvirus family associated with various illnesses, including infectious mononucleosis.

The virus is also linked to nasopharyngeal cancer and Burkitt lymphoma.

It is named for Anthony Epstein and Yvonne Barr, who identified the virus in tissue samples sent from Uganda in 1964 by Denis Burkitt (1911–1993), for whom Burkitt lymphoma was named.

EBV is also called human herpesvirus 4 or HHV-4.

DEMOGRAPHICS

EBV appears in nearly all world regions and is considered among the most common infectious viruses known to humankind.

Its genetic diversity is probably even greater than was thought when it was first identified.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) evaluates that 95 percent of adult Americans between the ages of 35 and 40 years have been infected with EBV, even if they have not shown symptoms; it is less prevalent in children and teenagers.

The CDC also estimates that at least 25% of teenagers and young adults infected with EBV develop mononucleosis.

This pattern continues all over other wealthy Western countries but apparently, does not hold in non-developed regions such as Asia and Africa.

In Africa, most of the children have been infected by EBV by the age of three years.

EBV is associated with some cancers, but the infection rarely leads to cancer. Worldwide, EBV-related cancers account for 1.5% of all cancers and 1.8% of all cancer deaths.

About 8%–10%of stomach cancers and nearly all nasopharyngeal cancers—cancers affecting the region of the throat behind the nose—are associated with EBV.

Several lymphomas are also associated with EBV. This relationship is not completely understood, however.

In the case of some lymphomas, it is thought that the virus infects B lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, and changes the behavior of the cells.

In January 2013, researchers discovered a preliminary link between certain characteristics of human chromosome 6 and the ability of EBV to result in cancer and other serious diseases.

Research from 2019 shows that different strains of the EBV virus lead to different disease courses.

These conclusions could help improve understanding of the relationship between EBV infection and cancer risk.

The nasopharyngeal tumor is uncommon in the West but more prevalent in the Far East. It affects three times as many men as women and usually occurs in adults between the ages of 40 and 60.

This type of cancer is diagnosed in fewer than 1 in every 100,000 Caucasians but up to 21 persons per 100,000 in mainland China.

It also occurs more frequently in Native Americans in Greenland and Alaska and Tunisians, with about 20 cases per 100,000 people per year.

The incidence rate in adults of Asian descent in the United States is 3.1 cases per 100,000 persons. For African Americans, the incidence rate is 0.9 per 100,000 people.

Nasopharyngeal cancer accounts for less than 1% of malignancies in children. It affects 1 in every 100,000 children in North America and Europe each year but between 8 and 25 of every 100,000 children in Asia.

Although not everyone who has EBV infection develops nasopharyngeal cancer, nearly everyone with this type of cancer has signs of EBV infection in their blood samples upon a cancer diagnosis.

Other cancers that may be associated with EBV include Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, including Burkitt lymphoma.

A history of infectious mononucleosis is a risk factor for Hodgkin lymphoma.

DESCRIPTION

Herpes viruses have long been known. The name derives from the Greek adjective Herpestes, which means creeping.

Many herpesvirus species appear to establish a lifelong presence in the human body, remaining dormant for long periods and becoming active for often inexplicable reasons.

EBV is one of several members of the herpes virus family that share similar symptoms.

Others add varicella-zoster virus—the cause of chickenpox and shingles—and the herpes simplex virus main culprit for both cold sores and genital herpes.

EBV is usually transmitted through saliva but not blood and is not normally an airborne infection.

Individuals with EBV infections typically display some elevation in the white blood cell count and a noticeable increase in lymphocytes—white blood cells associated with the immune response of the body.

Infectious mononucleosis usually lasts from one to two months. Symptoms include fever, malaise, sore throat, swollen glands, and (sometimes) swollen spleen and/or liver.

EBV infections that lead to Burkitt lymphoma in Africa typically affect the jaw and mouth area. In contrast, the (sporadic) cases of Burkitt lymphoma found in developed countries are more apt to manifest as tumors in the abdominal region, most commonly in the intestines, kidneys, or ovaries.

CAUSES AND SYMPTOMS

EBV and mononucleosis

EBV is normally transmitted by contact with the saliva of an infected person; it is not ordinarily transmitted through the air.

The virus takes about four to six weeks to incubate, and thus infected persons can spread the disease to others over a period of several weeks.

After entering the patient’s mouth and upper throat, the virus infects B cells, a white blood cell created in the bone marrow.

The infected B cells are then carried into the lymphatic system, affecting the liver and spleen and cause the lymph nodes to swell and enlarge.

The infected B cells are also responsible for the fever, swelling of the tonsils, and sore throat that characterize mononucleosis.

Most people who become infected with EBV do not display symptoms, however. In children, EBV infection is usually asymptomatic; when symptoms are present, they cannot distinguish from routine mild childhood infections.

Teenagers who were not exposed to EBV in childhood have a 25% chance of developing infectious mononucleosis (IM) from EBV.

The most common symptoms of IM in teenagers are fever, sore throat, and swollen lymph glands. The patient’s spleen and liver may be enlarged.

Once the symptoms of mononucleosis disappear, the EBV virus remains in a few cells in the patient’s throat tissues or blood for the remainder of the person’s life.

The virus occasionally reactivates and may appear in saliva samples without causing new symptoms.

EBV infection is not associated with pregnancy complications such as miscarriage or congenital disabilities.

EBV and cancer

EBV has become associated consistently with nasopharyngeal cancers in the United States and Asia (especially China) and Burkitt lymphoma in Africa and Papua New Guinea.

According to the CDC, EBV is not the sole cause of these malignancies but does play an important role in their development.

Much research is devoted to understanding the mechanism that permits EBV to produce such diverse illnesses in so many different regions.

The higher rate of nasopharyngeal cancer in Asia, for example, maybe attributed to the interaction of EBV with chemicals called nitrosamines that are used in the preparation of salted fish and other preserved foods popular in the region.

The interaction may trigger changes in cells that lead to cancer. As of 2020, the World Cancer Research Fund International was supporting research on this connection.

It is known that EBV is one of the herpes viruses that remain in the human body for life.

Under certain conditions that are still not well understood, EBV alters white blood cells normally associated with the immune system, changing the B cells (white blood cells normally associated with making antibodies) and causing them to reproduce uncontrollably.

EBV can bind to these white blood cells to produce a solid mass made up of B cells (Burkitt lymphoma) or to the mucous membranes of the mouth and nose and cause nasopharyngeal cancer.

Since Burkitt lymphoma typically occurs in people living in moist, tropical climates, the same regions where people usually contract malaria, some doctors speculate that the immune system is altered by its response to malaria.

When EBV infection occurs, the altered immune system reacts by producing a tumor.

DIAGNOSIS

A patient infected by EBV will have an increased number of white blood cells in the blood sample, an increased number of abnormal white blood cells, and antibodies to the Epstein-Barr virus.

These antibodies can be detected by a test called the monospot test, which produces results within a day but may not be accurate during the first week of the patient’s illness.

Another blood test for EBV antibodies takes longer to perform but gives more accurate results within the first week of symptoms.

When diagnosing cancers such as lymphomas and nasopharyngeal cancers, doctors always consider a patient’s medical history, along with laboratory results and a physical examination.

Information about the history of known EBV infection or mononucleosis can help the doctor determine whether a patient might have cancer linked to the virus.

TREATMENT

Because EBV infections result from viruses, antibiotics, which fight bacterial infections, are ineffective.

A great part of research is dedicated to developing a vaccine effective against both the virus and cancer.

Treatment for mononucleosis caused by EBV consists of self-care at home until the symptoms abate.

Patients should rest in bed if possible and drink plenty of fluids. Nonaspirin pain relievers like Advil or Tylenol help reduce fever and relieve muscle aches and pains.

Throat lozenges or gargling with mild saltwater may help ease the sore throat that usually accompanies mononucleosis.

Until researchers can pinpoint the factors that link EBV to the development of specific cancers, the presence of an EBV infection does not alter the course of cancer treatment.

Patients will be treated according to the type and stage, along with other considerations such as their age and overall health.

Alternative

Patients infected with EBV and ill with mononucleosis should remain hydrated and rest until the disease runs its course.

Any cancer patient who seeks alternative and complementary therapies should discuss the treatments with his or her cancer care team.

PROGNOSIS

In the United States, the 5-year relative survival rate for nasopharyngeal cancer is 60%.

The prognosis for late-stage nasopharyngeal cancer associated with EBV in adults is around 48% if the tumor has spread to remote parts of the body.

The survival rates for children receiving multimodal treatment, like radiation and chemotherapy, are above 80%.

PREVENTION

No vaccine prevents EBV infection or cancer from EBV; however, a candidate vaccine and an EBV immunotherapy product were in phase II clinical trials in 2020.

In addition, because people often lack symptoms, the spread of the virus and mononucleosis are difficult to control.

As a precaution, patients diagnosed with mononucleosis should avoid close personal contact with others and wash all eating utensils separately for several days following the end of their fever. Complete isolation is not necessary.

Because EBV remains in the body once the symptoms of mononucleosis disappear, people who have been diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis should refrain from blood donation for at least six months after the initial symptoms become evident.

Until the link between EBV and cancer is better understood or a vaccine is developed and approved, specific measures to prevent cancers associated with EBV are not recommended beyond standard prevention guidelines associated with cancer risk.

Resources

Bast, Robert C., et al., editors. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 9th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2017.

Minarovits, Janos, and Hans Helmut Niller, editors. Epstein–Barr Virus: Methods and Protocols. New York: Humana Press, 2017.

Shors, Teri. Understanding Viruses. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2017.

Stern, Scott D. C., Adam S. Cifu, and Diane Altkorn, editors. Symptom to Diagnosis: An Evidence-Based Guide. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2019.

Chan, Allen K. C., et al. “Analysis of Plasma Epstein–Barr Virus DNA to Screen for Nasopharyngeal Cancer.” New England Journal of Medicine 377 (2017): 513–22.

Farrell, Paul J. “Epstein–Barr Virus and Cancer.” Annual Reviews of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 14 (2019): 29–53.

Guidry, J. T., C. E. Birdwell, and R. S. Scott. “Epstein–Barr Virus in the Pathogenesis of Oral Cancers.” Oral Diseases 24, no. 4 (2017): 497–508.

Naseem, Madiha, et al. “Outlooks on Epstein–Barr Virus–Associated Gastric Cancer.” Cancer Treatment Reviews 66 (2018): 15–22.

Nishikawa, Jun, et al. “Clinical Importance of Epstein–Barr Virus–Associated Gastric Cancer.” Cancers 10, no. 6 (2018).

“About Epstein–Barr Virus.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/epstein-barr/about-ebv.html (accessed March 23, 2020).

“Hodgkin Lymphoma Risk Factors.” American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/hodgkindisease/detailedguide/hodgkin-disease-risk-factors (accessed March 23, 2020).

Lin, Ho-Sheng. “Malignant Nasopharyngeal Tumors.” Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/848163-overview (accessed March 23, 2020).

American Cancer Society, 250 Williams St. NW, Atlanta, GA 30303, 800-227-2345, https://www.cancer.org

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1600 Clifton Rd., Atlanta, GA 30329-40272, 800-232-4636, https://www.cdc.gov

National Cancer Institute, BG 9609 MSC 9760, 9609 Medical Center Dr., Bethesda, MD 20892, 800-422-6237, https://www.cancer.gov